Use that Pencil for Pizza!

By Hope Wallace

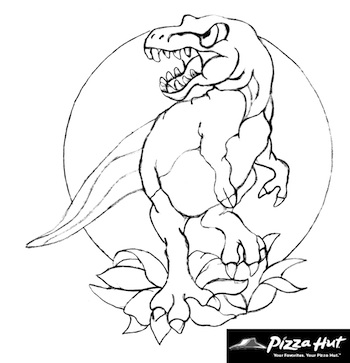

We received some really cool drawings for our last Pencil for Pizza contest for kids 5 to 18 so we’ve decided to keep offering it! It’s great to see so many of your different styles and ideas. Remember you can use paint, pencil, colored pencil, collagé or whatever media you are most comfortable with. We encourage you to interpret the drawing with your own style, color or technique. Maybe T-Rex needs a Halloween costume or some dental work!

Take an unlined piece of paper and draw the “Draw this!” image, then drop it off to us here at the Wassenberg Art Center by October 30 for a chance to win a FREE any size/any kind pizza from Pizza Hut. While tracing can be good, we require you to do your own thing. If the drawing appears to be traced it will be removed from the running. Please put your name, age, where you live, phone and email address on the back of your drawing. Winning drawings will be featured here.

More classes are evolving and being introduced. We add new classes to our roster all the time, so check them out. Call next week for information on the Silk Scarf Painting and Beginning Landscapes in Oil classes. Classes fill up quickly so register early.

On November 5, 9 a.m–1 p.m. Jodi Hattery of the Wassenberg Camera Club will be offering mini-photo sessions here at the Wassenberg Art Center for the upcoming holidays. Proceeds benefit the Camera Club. There are several packages to choose from so book your appointment early. You can bring your children, yourself or your pets (ON leash and up to date on Rabies shots, please!). Please contact Jodi at: 419 234 8587 or Jodi@hatteryphotograhy.net to reserve your time.

Contact the art center at 419.238.6837 or via wassenberg@embarqmail.com. The Wassenberg Art Center is located at 643 S. Washington St. in Van Wert.

African masks unmasked

By Kay Sluterbeck

Many people in Western society think of a mask as a disguise or a way to play the role of another person or animal at Halloween. But when Pablo Picasso first saw masks and sculptures from West Africa, he was amazed by their stylization and vitality. He began to use elements from these masks in his own artwork, beginning with “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” in which the faces of the women in the picture are masklike and very much resemble West African carvings. Spurred on by Picasso and other artists, movements such as cubism, fauvism and expressionism have often taken inspiration from the vast array of traditional African masks.

Many consider masks to be works of art. However, African masks were, and most still are, created for a particular purpose – usually as a link with the supernatural. Each mask has a specific symbolic meaning. Some masks are part of a complete and highly complex costume. The art of mask-making is passed on from father to son, and special status is given to the artists who make masks and to the people who wear them in ceremonies.

In many traditional African cultures, it is believed that when a dancer puts on a mask, he becomes the spirit represented by the mask. In essence, the dancers become mediums that allow the community and the spirit world to interact. Masked dances are part of weddings, funerals, initiations, and other community events. Masks are also used for other purposes, such as administering justice and in teaching young people laws, history, and traditions.

Because the masks have strong spiritual meanings, only selected people are allowed to wear them. In many cases only men can wear masks, most specifically men of high social status or elders of the tribes. Some masks may only be worn by chieftains and kings. Others are reserved for witch doctors or warriors.

African masks may be based on the human face, or they may represent an animal – sometimes in a highly abstract form. The extreme stylization of these masks is due to the fact that in most African cultures the subject of the mask is not a person or an animal, but the essence of that being. For example, the nwantantay masks of the Bwa people are intended to represent the flying spirits of the forest. Because these spirits are believed to be invisible, the masks that represent them are carved in abstract, completely geometrical forms.

Masks may also represent moral traits, ideal feminine beauty (usually only men are allowed to wear these masks), or dead ancestors either ordinary or legendary. Most masks are made of wood, but a wide variety of other materials may be used, including lightweight stone, metals such as copper or bronze, fabric, and pottery. Some masks are painted with natural materials, and may include seeds, beads, feathers, animal hair, and shells, among other things. Long straw or raffia fringes are sometimes attached to the base of the mask to completely hide the identity of the person wearing it.

Because Westerners appreciate African masks as decorative artworks, one can now purchase commercialized masks in tourist markets and shops across Africa, as well as in “ethnic” shops in the U.S. and Europe. The consequence of this commercial mass production has caused the traditional mask-makers to slowly lose their privileged status. Although in most cases commercial masks are more or less accurate reproductions of the traditional masks, the logistics of mass production make it harder to identify the actual cultural origins of masks sold as souvenirs and art pieces. For example, one small area with many skilled carvers may turn out masks that originated in a number of different cultures spread over a wide area.

Whether a mask is used for ritual purposes or as an artistic decoration, it is a unique and specialized art form that can be appreciated on many levels.

POSTED: 10/12/11 at 12:59 pm. FILED UNDER: What's Up at Wassenberg?