New Brumback Library series begins

Editor’s note: this year the Brumback Library will be celebrating 125 years of service to the community. Each month, library officials will tell the story of The Brumback Library, chapter by chapter. It starts with the story with the man who began it all, John Sanford Brumback. This chapter is told by his great-great-grandson, D.L. Brumback.

By D.L. Brumback

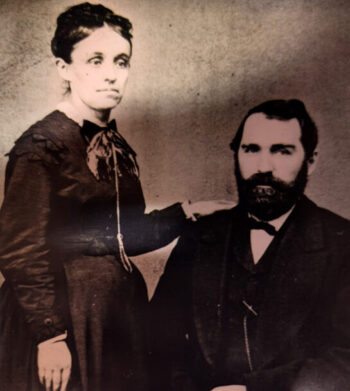

When I was a boy, the stories about my great-great-grandfather always began the same way: lamplight, a small hand on a ledger, a quietness that felt like thought. My family still points to a faded portrait and says, “There he is, counting coins and counting lessons.”

To me, that image is less about thrift and more about purpose. John Sanford Brumback learned early that a book could do useful work: teach a clerk arithmetic, show a gardener how to graft, help a teacher plan a lesson. Books, for him, were tools, not trophies.

He carried that idea through his life. People who knew him called him deliberate and humane. He kept modest habits but thought in big, durable ways. He wasn’t interested in a ribbon-cutting that made the papers and then faded. What haunted him was how to make learning available to the boy who must milk cows before school, or the woman who could not afford a subscription. His answer wasn’t rhetoric, it was a plan: build something that would last, and design it to be shared beyond a single main street.

Over family holiday dinners, we learned his reasoning at family tables. He pictured a library not as ornament but as infrastructure, like a bridge that carries people to new places without asking them to leave home. He wanted a library that would cross township lines, reach into schoolhouses and farmhouses, and be staffed so anyone who could not read well could be guided to the right book. That practical generosity, private means turned into public access, became the quiet creed we inherited.

There was moral economy in his choices. Where some donors give a building and expect the city to maintain the plaque, J.S. insisted on arrangements that made upkeep the community’s duty: a durable building, a plan for trained librarians, and a funding model that would not let the place rot when officials changed. He thought of succession as a machine you could build; parts that fit together so the machine would run after he was gone.

Telling his story now, I feel how small acts added up to something large. A ledger, a horticulture pamphlet, a grammar book, these were seeds of a public idea. J.S.’s dream was plain and stubborn: make books useful, make them available, and bind the community to their care. That thread runs through everything that follows, the reading rooms, the legal work, and the contract that turned private grief into a county promise.

The Parlor That Read: The Reading Room That Became a Cause

Before cornerstone ceremonies and trustees’ signatures, there was a parlor with a lamp and a list tacked to the shop window. The county’s earliest library life grew out of small, ordinary acts: women who met to read and stitch clippings into scrapbooks, a teacher who left books at the school for students, a grocer who kept a ledger of which titles he loaned to neighbors. Modest subscription funds paid for candles and covers and, more importantly, taught people to treat books as shared resources.

I grew up hearing of those women’s reading circles as if they were town saints. They ran bazaars, kept ledgers of borrowers, and argued gently about who would steward the collection next. The reading room became a civic crossroad: farmers’ wives learned recipes and seed techniques, clerks found textbooks, the elderly found someone to read to them on stormy afternoons. When people of different walks of life sat down to the same page, something public was being born.

Those volunteers learned the craft of libraries in miniature – how to catalogue, how to rotate a popular book so more could read it, how to keep a ledger honest. By the time J.S.’s bequest arrived, the town had the habits to sustain something larger. The reading-room had taught the county to expect sharing: it was easier to imagine a county library because neighbors had already practiced the rules of sharing. It was an incubator and a proof: ordinary people had already made the case that shared books changed lives.

This is where the story pauses, just before sentiment met structure. By the time my great-greatgrandfather’s vision intersected with the county’s readiness, the question was no longer whether a county library should exist, but how it could be built to endure. Turning generosity into institution would require law, compromise, and shared responsibility—a story that continues in the next month when we explore how The Brumback Library became the first county library in the country.

Source: The County Library, by Saida Brumback Antrim, (1914) Lamplight & Ledger: The Man Who Dreamed of Books

January at the Brumback Library

Our Winter Reading Program kicks off January 1 and runs through February 13 at all locations, inviting readers of all ages to participate. For every book read or listened to, patrons may enter a raffle to win prizes donated by local businesses. January also offers many ways to connect at the Library. Programs this month include HiSTORIES, Lima Symphony Storytime, educational presentations, teen and tween activities, a speed puzzle competition, bingo, and community events across our locations in Van Wert, Convoy, and Middle Point. The Van Wert Chess Club continues to meet weekly in the Reading Room, alongside regular storytimes and monthly Silent Book Club gatherings. Find dates and times for all events on our website calendar.

POSTED: 01/05/26 at 9:45 pm. FILED UNDER: News